Women in American history

There are so many important women in the history of the United States. Some who you may be familiar with, but many you probably have never heard of.

This page is dedicated to sharing some of their stories.

Note: It is important to share the truth of these histories. If a woman did help to advance women in other areas but was racist, this is mentioned in their history. Since so many of those women's contributions are already well known, but their racism may not be, we thought it was important to share the whole story.

Trailblazers in STEM

Dr. James Barry/Margaret Ann Bulkley - (1789 –1865)

Dr. James Barry/Margaret Ann Bulkley - (1789 –1865)

Dr. James Barry/Margaret Ann Bulkley - (1789 –1865)

Dr. James Barry (1789(?) –1865) was born Margaret Ann Bulkley around 1789 in County Cork, Ireland, at a time when women were barred from most formal education, and were not allowed to practice medicine. As Dr. James Barry, Margaret was a skilled military surgeon who rose to the rank of Inspector General in charge of military hospitals, the second-highest medical office in the British Army.

Barry’s journey began when Margaret’s mother Mary Ann’s brother James Barry died in 1806.

In 1809, Margaret Bulkley donned an overcoat, 3-inch high shoe inserts and began identifying herself as James Barry. Moving to Edinburgh, Barry enrolled in medical school and altered his age to match his young look. Despite some calling Barry’s age into question, Barry received a degree in medicine at the age of 22.

Barry began his military career in 1813 as a Hospital Assistant in the British Army, and was soon promoted to Assistant Staff Surgeon. He served in Cape Town, South Africa, for 10 years where he befriended the governor, Lord Charles Somerset. Some believe Somerset knew Barry’s secret.

Barry was a skilled surgeon, performing the first recorded caesarean section by a European in Africa in which both the mother and child survived the surgery. Barry was also dedicated to social reform, speaking out against the unsanitary conditions and mismanagement of barracks, prisons and asylums. During his 10-year stay, he arranged for a better water system for Cape Town. As a doctor, he treated the rich and the poor, the colonists and the slaves.

Barry continued to climb the ranks as he traveled the world. In 1857, he reached the rank of Inspector General in charge of military hospitals. In that position, he continued his fight for proper sanitation, also arguing for better food and proper medical care for prisoners and lepers, as well as soldiers and their families.

Dr. James Barry died from dysentery on July 25, 1865. Barry’s last wishes were to be buried in the clothes he died in, without his body being washed—wishes that were not followed. When the nurse undressed the body to prepare it for burial, she discovered two things: female anatomy and tell-tale stretch marks from pregnancy.

The secret was made public after letters between the General Register Office and Barry’s doctor, Major D. R. McKinnon, were leaked. In these letters, Major McKinnon, who signed the death certificate, said it was “none of my business” whether Dr. James Barry was male or female.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910)

Dr. James Barry/Margaret Ann Bulkley - (1789 –1865)

Dr. James Barry/Margaret Ann Bulkley - (1789 –1865)

Elizabeth Blackwell (February 3, 1821 – May 31, 1910) was an English-American physician.

On January 23, 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to graduate from medical school and become a doctor in the United States. She graduated from Geneva College, NY with the highest grades in her entire class.

She went on to start the New York Infirmary for Women and Children with her sister Dr. Emily Blackwell and colleague Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, whose mission included providing positions for women physicians. During the Civil War, she and her sister trained nurses for Union hospitals.

In 1868, Blackwell opened a medical college in New York City and in 1875, she became a professor of gynecology at the new London School of Medicine for Women.

Margaret E. Knight (1838 - 1914)

Dr. James Barry/Margaret Ann Bulkley - (1789 –1865)

Margaret Knight (Feb. 14, 1838 - Oct. 12, 1914) was an American inventor.

When she was working at a textile mill as a young teenager, she invented a shuttle restraint system to prevent worker injuries.

Her safety device became a standard fixture on looms across the country. At the time she was unaware of the patent system and did not receive any compensation or recognition for her invention.

In 1867, Knight began working at the Columbia Paper Bag Co. in Springfield, Massachusett. She wondered if she could devise a way to automate the bag-making process. She began building a machine that would automatically feed, cut, and fold the paper as well as form the squared bottom of the bag.

Just one year later, in 1868, Knight’s machine was fully operational and had significantly improved both the company’s output and the uniformity of its paper bags.

This time she knew Knight knew she needed to apply for a patent on her machine. However, Charles Annan, a man who worked in the machine shop that manufactured it, attempted to steal her design.

In court, Annan claimed that as a woman, Knight “could not possibly understand the mechanical complexities of the machine.” Knight quickly disproved his argument by providing the original blueprints of the machine’s design. She won the case and received a patent on her invention in 1871.

Knight co-founded the Eastern Paper Bag Co. in Hartford, Connecticut. She continued to invent throughout her life, and by the time she passed away in 1914, she had patented 26 inventions, ranging from a window frame to a sole-cutting machine for shoemaking, to a compound rotary engine.

Letitia Mumford Geer (1852– 1935)

Letitia Mumford Geer (1852– July 18, 1935) was an American nurse who invented the one-hand medical syringe.

Syringes at the time were awkward two-handed devices: hard to use, hard to control, and not exactly user-friendly in a crisis.

On February 12, 1896, Geer filed for a patent for the one-handed medical syringe design. Her design was given a patent three years later.

Geer designed her syringe with a distinctive U-shaped handle on the plunger rod. This design gave a secure grip and the ability to administer a controlled, single-handed operation injection.

In 1904, Geer founded the Geer Manufacturing Company to develop her design for medical syringes. Her invention inspires modern-day syringes.

Other companies started to produce syringes that were copies of Geer's design.

Annie Cannon (1863–1941)

Annie Jump Cannon (December 11, 1863 – April 13, 1941) was an American astronomer who was instrumental in the development of contemporary stellar classification. During her career, Cannon helped women gain acceptance and respect within the scientific community.

Cannon's mother was the first person to teach her the constellations and encouraged her to follow her interests. Cannon and her mother used an old astronomy textbook to identify stars seen from their attic.

In 1880, Cannon went to Wellesley College in Massachusetts, where she studied physics and astronomy under Sarah Frances Whiting, one of the few women physicists in the United States at the time. She graduated as valedictorian with a degree in physics in 1884 and returned home to Delaware.

In 1893, Cannon was stricken with scarlet fever that rendered her nearly deaf.

Cannon enrolled at Radcliffe College in 1894 as a "special student", continuing her studies of astronomy. In 1907, Cannon received her master's degree from Wellesley College.

In 1896, Cannon became a member of the Harvard Computers, a group of women hired by Harvard Observatory director Edward C. Pickering to complete the Henry Draper Catalogue, with the goal of mapping and defining every star in the sky to a photographic magnitude of about 9.

Men operated the telescopes and took photographs while the women examined the data, carried out astronomical calculations, and cataloged the photographs.

When Cannon first started, she classified 1,000 stars in three years, but by 1913, she was able to work on 200 stars an hour. Cannon could classify three stars a minute just by looking at their spectral patterns and, if using a magnifying glass, could classify stars down to the ninth magnitude, around 16 times fainter than the human eye can see. Her work was highly accurate.

In 1901, Cannon published her first catalog of stellar spectra.

In 1911 she was made the Curator of Astronomical Photographs at Harvard. In 1914, she was admitted as an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society. In 1921, she was awarded an honorary doctor's degree in math and astronomy from Groningen University.

On May 9, 1922, the International Astronomical Union passed the resolution to formally adopt Cannon's stellar classification system; with only minor changes, it is still being used for classification today.

In 1925, she became the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate of science from Oxford University.

An asteroid and a lunar crater are named after her.

Annie Jump Cannon's career in astronomy lasted for more than 40 years, until her retirement in 1940. After retirement she continued to actively work on astronomy up until a few weeks before she died.

Susan La Flesche Picotte (1865-1915)

Susan La Flesche Picotte (June 17, 1865 – September 18, 1915) was the first Indigenous woman, to earn a medical degree.

She spent her life caring for her Omaha tribal community, serving more than 1,200 patients in the Omaha Reservation area.

She worked to improve the public health of the community, advocated for the interests of indigenous people, and helping other Omaha receive the money owed to them for the sale of their land.

She also founded the first private hospital on reservation land in Walthill, Nebraska .

Hallie M. Daggett (1878-1964)

Hallie M. Daggett (1878-1964)

Hallie M. Daggett (1878-1964)

Hallie M. Dagget (December 19, 1878 – October 19, 1964) was the first woman employed by the Forest Service as a lookout. She started work at Eddy's Gulch Lookout Station atop Klamath Peak (Klamath National Forest) in the summer of 1913. She continued to work as lookout for 14 years.

"Some of the Service men predicted that after a few days of life on the peak she would telephone that she was frightened by the loneliness and the danger, but she was full of pluck and high spirit...[and] she grew more and more in love with the work. Even when the telephone wires were broken and when for a long time she was cut off from communication with the world below she did not lose heart. She not only filled the place with all the skill which a trained man could have shown but she desires to be reappointed when the fire season opens this year." (American Forestry 1914)

Edith Clarke (1883 – 1959)

Hallie M. Daggett (1878-1964)

Hallie M. Daggett (1878-1964)

Edith Clarke (February 10, 1883 – October 29, 1959) was an American engineer and academic. She was the first woman to be professionally employed as an electrical engineer in the United States, and the first female professor of electrical engineering in the country.

She worked as a “computer,” someone who performed difficult mathematical calculations before modern-day computers and calculators were invented. Clarke struggled to find work as a female engineer instead of the ‘usual’ jobs allowed for women of her time, but became the first professionally employed female electrical engineer in the United States in 1922. She paved the way for women in STEM and engineering and was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2015.

Eloise Gerry (1885-1970)

Hallie M. Daggett (1878-1964)

Beulah Louise Henry (1887 - 1973)

Eloise Gerry (January 12, 1885 – 1970) was an influential research scientist whose work contributed greatly to the study of southern pine trees and turpentine production.

Gerry was the first woman appointed to the professional staff of the U.S. Forest Service at the Forest Products Laboratory in 1910, and one of the first women in the United States to specialize in forest products research.

During World War II, Gerry wrote wartime publications on defects in wood used for trainer aircraft and gliders. Following 44 years with the U.S. Forest Service, Gerry retired in 1954. Gerry died in 1970 at the age of 85.

Beulah Louise Henry (1887 - 1973)

Beulah Louise Henry (1887 - 1973)

Beulah Louise Henry (1887 - 1973)

Beulah Louise Henry (September 28, 1887 – February 1, 1973) was an American inventor.

Henry held 49 patents and developed over 110 inventions, advancing technology and breaking gender barriers.

Henry submitted her first patent, for a vacuum ice cream freezer, while still a college student in 1912. In 1924 she moved to New York City to found two companies to sell her many inventions.

One of Henry's most famous inventions is the "Double Chain Stitch Sewing Machine", a sewing machine that wouldn’t tangle the thread. Her invention doubled the speed of the typical sewing machine and allowed for the use of smaller threads while still making a strong stitch.

She also invented a "protograph," a typewriter that created four identical copies of a document without carbon paper.

At the time she was registering her patents, only 2% of all patents were registered by women. She is still considered one of the most successful female inventors of all time. Henry was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006.

Gerty Cori (1896-1957)

Beulah Louise Henry (1887 - 1973)

Dorothy Klenke Nash (1898 – 1976)

Gerty Theresa Cori (August 15, 1896 – October 26, 1957) was a Bohemian-Austrian and American biochemist. In 1947 she became the third woman to win a Nobel Prize in science, and the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, for her role in the "discovery of the course of the catalytic conversion of glycogen".

Image from the Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine

Dorothy Klenke Nash (1898 – 1976)

Beulah Louise Henry (1887 - 1973)

Dorothy Klenke Nash (1898 – 1976)

Dorothy Klenke Nash (October 24, 1898 – March 5, 1976) was the first American woman to become a neurosurgeon, and the only American woman neurosurgeon from 1928 to 1960.

She became senior surgeon and head of neurology at St. Margaret's Hospital in Pittsburgh in 1942, and served on the staffs of the Western Pennsylvania Hospital and the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. She taught neurosurgery at the University of Pittsburgh, and served as a delegate to the state medical society, representing the Allegheny County Medical Society. She was president of the Pittsburgh Neuropsychiatric Society in 1957 and 1958.

Maria Goeppert Mayer (1906-1972)

Maria Goeppert Mayer (1906-1972)

Maria Goeppert Mayer ( June 28, 1906 – February 20, 1972) was a German-American theoretical physicist . She became the first American woman to receive a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963. She shared the prize with J. Hans D. Jensen "for their discoveries concerning nuclear shell structure” and Eugene Paul Wigner "for his contributions to the theory of the atomic nucleus and the elementary particles, particularly through the discovery and application of fundamental symmetry principles".

Mollie Orshansky (1915-2006)

Maria Goeppert Mayer (1906-1972)

Mollie Orshansky (January 9, 1915 – December 18, 2006) was an American economist and statistician. Her work on poverty thresholds pioneered the way the U.S. Government defines poverty.

During the years 1963–65, she developed the Orshansky Poverty Thresholds, which are used in the United States as a measure of the income that a household must not exceed to be counted as poor.

She used the cost of a nutritionally adequate diet as the basis for a cost-of-living estimate, and to calculate a cost of living for families of different sizes and composition.

Her work provided a way to assess the impact of new policies on poor populations, which to this day remains a standard measure of new policies.

Ruth Rogan Benerito (1916-2013)

Ruth Rogan Benerito (1916-2013)

Ruth Mary Rogan Benerito (January 12, 1916 – October 5, 2013) was an American physical chemist and inventor.

Benerito saved the cotton industry in post-WWII America by discovering of a process to produce wrinkle-free, stain-free, and flame-resistant cotton fabrics. Benerito also developed a method to harvest fats from seeds for use in intravenous feeding of medical patients. She held 55 patents in total.

She worked at the USDA Southern Regional Research Center of the US Department of Agriculture in New Orleans for the majority of her career. After she retired from the USDA, she taught university courses for an additional eleven years,

Benerito received the Lemelson-MIT Lifetime Achievement Award for her contributions to the textile industry and her commitment to education.

Katherine Johnson (1918-2020)

Ruth Rogan Benerito (1916-2013)

Creola Katherine Johnson (August 26, 1918 – February 24, 2020) was an American mathematician whose calculations of orbital mechanics as a NASA employee were critical to the success of U.S. crewed spaceflights.

In 1962, Katherine Johnson performed the calculations for the NASA orbital mission, launching John Glenn as the first person into orbit and returning them safely.

During her 33-year career at NASA and The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the predecessor to NASA, she mastered complex manual calculations and helped pioneer the use of computers to perform the tasks. NASA noted her "historical role as one of the first African-American women to work as a NASA scientist".

Angeline Nanni (1918- 2019)

Angeline Nanni (August 2, 1918, August 27, 2019) was part of a group of women who deciphered codes connected to Soviet spy communications during and after World War II. She was part of a secretive effort known as the Venona Project.

She was working at her sisters' Blairsville beauty shop in 1945 when she heard of a government job opportunity in Washington, D.C. Nanni thought she'd check it out for a year.

"I just want to go see what's going on there," Nanni remembered telling her sisters.

Nanni later described the test she took to join the program.

“On a piece of paper before her were 10 sets of numbers, arranged in five-digit groups. The numbers represented a coded message. Each five-digit group had a secret meaning. Below that row of 50 numbers was another row of 50, arranged in similar groups. The supervisor told them to subtract the entire bottom row from the top row, in sequence. She said something about 'non-carrying.'

"Angie had never heard the word 'non-carrying' before, but as she looked at the streams of digits, something happened in her brain. She intuited that the digit 4, minus the digit 9, equaled 5, because you just borrowed an invisible 1 to go beside the top number. Simple! Angie Nanni raced through, stripping out the superfluous figures to get down to the heart of the message."

For nearly 40 years, Angie and her colleagues helped identify those who passed American and Allied secrets to the Soviet Union during and after World War II. Their work unmasked such infamous spies as the British intelligence officer Kim Philby, the British diplomat Donald Maclean, the German-born scientist Klaus Fuchs and many others. They provided vital intelligence about Soviet tradecraft.

In an interview with the Tribune-Review, Nanni was humble about her accomplishments, saying that she was simply doing her job alongside plenty of other women, many of whom became lifelong friends.

Julia Robinson (1919-1985)

Julia Hall Bowman Robinson (December 8, 1919 – July 30, 1985) was an American mathematician. She is known for her contributions to the fields of computability theory and computational complexity theory, most notably in decision problems. Her work on Matiyasevich's played a crucial role in its ultimate resolution.

In 1975, she was the first female mathematician to be elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

Robinson became the first female president of the American Mathematical Society in 1983, but was unable to complete her term due to leukemia.

"In 1982 I was nominated for the presidency of the American Mathematical Society. I realized that I had been chosen because I was a woman and because I had the seal of approval, as it were, of the National Academy. After discussion with Raphael, who thought I should decline and save my energy for mathematics, and other members of my family, who differed with him, I decided that as a woman and a mathematician I had no alternative but to accept. I have always tried to do everything I could to encourage talented women to become research mathematicians. I found my service as president of the Society taxing but very, very satisfying."

Robinson received the MacArthur Fellowship in 1983.

Lynn Margulis (1938 – 2011)

Lynn Margulis (March 5, 1938 – November 22, 2011) was an American evolutionary biologist, and was the primary modern proponent for the significance of symbiosis in evolution.

Margulis framed the current understanding of the evolution of cells with nuclei by proposing it to have been the result of symbiotic mergers of bacteria.

Her paper on the subject, "On the Origin of Mitosing Cells", appeared in 1967 after being rejected by about fifteen journals. Still a junior faculty member at Boston University at the time, her theory that cell organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts were once independent bacteria was largely ignored for another decade, becoming widely accepted only after it was powerfully substantiated through genetic evidence.

Margulis was also the co-developer of the Gaia hypothesis with the British chemist James Lovelock, proposing that the Earth functions as a single self-regulating system.

Her 1982 book Five Kingdoms, written with American biologist Karlene V. Schwartz, articulates a five-kingdom system of classifying life on Earth as animals, plants, bacteria (prokaryotes), fungi, and protoctists.

Margulis was elected a member of the US National Academy of Sciences in 1983. She was presented with the National Medal of Science in 1999. The Linnean Society of London awarded her the Darwin-Wallace Medal in 2008.

Sally Ride (1951-2012)

Sally Kristen Ride (May 26, 1951 – July 23, 2012) was an American astronaut and physicist. Born in Los Angeles, she joined NASA in 1978, and in 1983 became the first American woman and the third woman to fly in space, after cosmonauts Valentina Tereshkova in 1963 and Svetlana Savitskaya in 1982. She became the youngest American astronaut at the age of 32. She spent a total of more than 343 hours in space before leaving NASA in 1987, on the Space Shuttle Challenger.

Ride earned a Bachelor of Science degree in physics and a Bachelor of Arts degree in English literature in 1973, a Master of Science degree in 1975, and a Doctor of Philosophy in 1978.

She was selected as a mission specialist astronaut with NASA Astronaut Group 8, the first class of NASA astronauts to include women. She served as the ground-based capsule communicator for the second and third Space Shuttle flights, and helped develop the Space Shuttle's robotic arm. In June 1983, she flew in space on the Space Shuttle Challenger on the STS-7 mission. Her second space flight was the STS-41-G mission in 1984, also on board Challenger.

She is the first astronaut known to have been LGBTQ, a fact that she hid until her death in 2012.

Activists and Politicians

Abigail Adams (1744-1818)

Elizabeth Freeman (1744-1829)

Elizabeth Freeman (1744-1829)

Abigail Adams (November 22, 1744 – October 28, 1818) was the wife and closest advisor of John Adams, the second president of the United States, and the mother of John Quincy Adams, the sixth president of the United States.

On March 31, 1776, Abigail Adams wrote the following in a letter to her husband, founding father John Adams.

"I long to hear that you have declared an independency -- and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.

That your Sex are Naturally Tyrannical is a Truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend. Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity. Men of Sense in all Ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your Sex. Regard us then as Beings placed by providence under your protection and in immitation of the Supreem Being make use of that power only for our happiness."

Elizabeth Freeman (1744-1829)

Elizabeth Freeman (1744-1829)

Elizabeth Freeman (1744-1829)

Elizabeth (Bet) Freeman (1744(?) – December 28, 1829) was one of the first enslaved African Americans to file and win a freedom suit in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in Freeman's favor and found slavery to be in violation of the 1780 Constitution of Massachusetts. Her suit was later cited in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court review of another freedom suit by Quock Walker. When the court upheld Walker's freedom under the state's constitution, this ruling essentially ended slavery in Massachusetts.

Freeman was illiterate and left no written records of her life. What is known of her history has been pieced together from historical records and those who wrote down her story.

Freeman was born on April 4th 1744, enslaved by Pieter Hogeboom on his farm in Claverack, New York, and called Bet. When his daughter Hannah married John Ashley of Sheffield, Massachusetts, Hogeboom gave Bet, then around seven years old, to Hannah and her husband. Freeman remained with them until 1781, when she had a child, Little Bet. She is said to have married, though no marriage record has been located. It is said that her husband never returned from service in the American Revolutionary War.

Throughout her life, Bet exhibited a strong spirit and sense of self. In 1780, Bet prevented Hannah from striking a servant girl with a heated shovel; Bet shielded the girl and received a deep wound in her arm. According to Catharine Sedgwick’s account, Freeman said that "Madam never again laid her hand on Lizzy. I had a bad arm all winter, but Madam had the worst of it. I never covered the wound, and when people said to me, before Madam,—'Why, Betty! what ails your arm?' I only answered—'ask missis!' Which was the slave and which was the real mistress?"

John Ashley’s house was the site of many political discussions and the probable location of the signing of the Sheffield Declaration, which predated the United States Declaration of Independence.

In 1780, Freeman either heard the newly ratified Massachusetts Constitution read at a public gathering in Sheffield or overheard her enslaver talking at events in the home, in particular the following statement:

:All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness."

Having heard this, she approached lawyer Theodore Sedgwick to help her sue for freedom in court. According to Catherine Sedgwick's account, she told him: "I heard that paper read yesterday, that says, all men are created equal, and that every man has a right to freedom. I'm not a dumb critter; won't the law give me my freedom?" After much deliberation, Sedgwick accepted her case, as well as that of Brom, another of Ashley’s slaves. Brom, an enslaved male, was probably added to the case to strengthen it as women had very limited legal rights at the time.

Sedgwick enlisted the aid of another lawyer, Tapping Reeve.

The case of Brom and Bett v. Ashley was heard in August 1781 by the County Court of Common Pleas in Great Barrington. Sedgwick and Reeve asserted that the constitutional provision that "all men are born free and equal" effectively abolished slavery in the state. It is notable that while arguing for his right to own Brom and Bett in court, Ashley described them as his “servants for life”, rather than slaves. When the jury ruled in Bett's favor, she became the first African-American woman set free under the Massachusetts state constitution.

The jury found that "Brom & Bett are not, nor were they at the time of the purchase of the original writ the legal Negro of the said John Ashley." The court assessed damages of thirty shillings and awarded both plaintiffs compensation for their labor. Ashley initially appealed the decision but a month later dropped his appeal.

After the ruling, Bet took the name Elizabeth Freeman. Although Ashley asked her to return to his house and work for wages, she chose to work in Sedgwick's household. She worked for his family until 1808 as a senior servant and governess to the Sedgwick children. She had a close relationship with the children and one of the children, Catharine Sedgwick, later wrote an account of her governess's life.

After the Sedgwick children were grown, Freeman moved into her own house on Cherry Hill in Stockbridge, near her daughter, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Freeman died in December 1829 and was buried in the Sedgwick family plot in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Freeman remains the only non-Sedgwick buried in the Sedgwick plot.

Sybil Ludington (1761–1839)

Elizabeth Freeman (1744-1829)

Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814-1904)

Sybil Ludington (April 5, 1761 – February 26, 1839) was an American woman who rode to muster militia troops during the American Revolutionary War at the age of 16. On the night of April 26, 1777, Sybil Ludington rode 40 miles to muster local militia troops in response to a British attack on the town of Danbury, Connecticut.

She traveled twice the distance that Paul Revere rode during his famous ride and alerted nearly the entire regiment of 400 Colonial troops. Following the battle, General George Washington personally thanked Sybil for her service and bravery.

Sybil was the oldest of Colonel Ludington's twelve children. His militia troops had disbanded for the planting season when he heard that British troops were marching towards Danbury, Connecticut. Sybil volunteered to ride to rally the militia to be at his house by daybreak.

At 9 pm and in the middle of heavy rain, she mounted her horse, Star, and set off. She rode from her family's farm in Kent, south to the village of Carmel, down to Mahopac, then west to Mahopac Falls, north to Kent Cliffs and Farmers Mills, and north to Stormville before returning south to the farm. She used a stick to bang on the shutters of homes, yelling "The British are burning Danbury!" By the time she returned home, most of the four hundred soldiers were on their way.

While her father’s troops were not able to save Danbury from being burned, they were able to join the Continental Army at the Battle of Ridgefield the following day to drive General William Tryon back to the British fleet at Long Island Sound. The British raid also led to a surge of support for the Patriot cause, and 3,000 local residents joined up.

Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814-1904)

Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814-1904)

Mary Ellen Pleasant (August 19, 1814 – January 11, 1904) was an American entrepreneur, financier, real estate magnate and abolitionist. She was the first self-made millionaire of African-American heritage.

She identified herself as "a capitalist by profession" in the 1890 United States census. Her aim was to earn as much money as she was able to help as many people as she could. With her riches she was able to provide transportation, housing, and food for survival. She trained people how to stay safe, succeed, carry themselves, and more. The "one woman social agency" served African Americans before and during the Civil War, as well as meeting a different set of needs after Emancipation.

She worked on the Underground Railroad and expanded it westward during the California Gold Rush era. She was a friend and financial supporter of John Brown and was well known among abolitionists.

Pleasant’s wealth allowed her to give generously to her community. She contributed to the Athenaeum Building, a library and meeting place for the city’s Black population; she also supported the Black press and the American Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.

She also fought civil rights battles. After a streetcar driver refused to stop for her, even though there was room in the car and she already had tickets, she sued the streetcar company for denying service to Black citizens. The case went all the way to the California Supreme Court, which declared segregation on streetcars to be unconstitutional.

Realizing that she was in a tenuous position as a black woman,she sought ways to blend in to the culture of the times. Long after she became wealthy, she portrayed herself as just a housekeeper and a cook, using these roles to get to know wealthy citizens and gain information for her investments. In the 1870s, she met Thomas Bell, a wealthy banker and capitalist. She built a large mansion that was portrayed as the Bells' residence and she assumed the role of housekeeper for the Bells, but actually ran the household.

At her request, her tombstone describes her as “a friend of John Brown.”

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906)

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) was born in Massachusetts and was raised a Quaker. One of the main beliefs of the Quakers is “the equality of all people before God”.

During her life, she fought for the abolition of slavery and for women's rights.

Her family home in Rochester, New York, served as a meetinghouse almost every Sunday, and abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison often attended these meetings.

In 1863, Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucy Stone formed the Women’s Loyal National League to press for an amendment to abolish slavery. This goal was finally realized with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

In 1851, Anthony met Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the two suffragists worked to gain independence and equality for women fo the rest of their lives. She traveled around the country advocating for women’s rights and lobbied Congress every year until her death.

In 1856, she served as an American Anti-Slavery Society agent, making speeches, organizing meetings, and distributing pamphlets.

In 1868 the suffrage movement divided over race.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Anthony believed educated white women deserved to vote before Black women. Though Anthony had previously lobbied for the abolition of slavery, she still adopted the racist positions used by many other white women at that time to support her goal of women’s suffrage.

She died in 1906, fourteen years before women were given the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

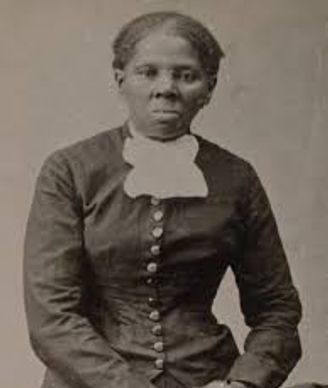

Harriet Tubman (1822-1913)

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, c. March 1822[1] – March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. After escaping slavery in 1849, Tubman made 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including her family and friends, using the network of antislavery activists and safe houses known collectively as the Underground Railroad.

Tubman travelled by night and in extreme secrecy, and said she "never lost a passenger". After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, she helped guide escapees farther north into Canada, and helped newly freed people find work. Tubman met John Brown in 1858, and helped him plan and recruit supporters for his 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry.

During the American Civil War, she served as an armed scout and spy for the Union Army. For her guidance of the raid at Combahee Ferry, which liberated more than 700 enslaved people, she is widely credited as the first woman to lead an armed military operation in the United States.

Tubman received little pay for her Union military service. She was only occasionally compensated for her work as a spy and scout, and her work as a nurse was entirely unpaid. For over three years of service, she received a total of $200. Her unofficial status caused great difficulty in documenting her service, and the U.S. government was slow to recognize any debt to her. Meanwhile, her humanitarian work for her family and the formerly enslaved kept her in a state of constant poverty.

In her later years, Tubman was an activist in the movement for women's suffrage, traveling to New York, Boston and Washington, D.C., to speak in favor of women's voting rights. When the National Federation of Afro-American Women was founded, Tubman was the keynote speaker at its first conference in 1896. When the Federation was merged into the National Association of Colored Women, Tubman attended that organization's second conference in 1899.

She died of pneumonia on March 10, 1913 and was buried with semi-military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn.

Victoria Woodhull (1838-1927)

Helen Hamilton Gardener (1853-1925)

Seraph Young Ford (1846–1938)

Victoria Claflin Woodhull (September 23, 1838 – June 9, 1927), was an American leader of the women's suffrage movement who ran for president of the United States in the 1872 election. While historians and authors agree that Woodhull was the first woman to run for the presidency, some do not call it a true candidacy because according to the Constitution she would have been too young to be President if elected.

Woodhull believed in free love and that women should have the right to divorce without being ostracized by society. Woodhull also fought against the hypocrisy of society's tolerating married men who had mistresses and engaged in other sexual dalliances, while stigmatizing women for the same actions.

Woodhull, with sister Tennessee (Tennie) Claflin, became the first female stockbrokers and in 1870 they opened a brokerage firm on Wall Street, Woodhull, Claflin & Company, with the assistance of the wealthy Cornelius Vanderbilt.

Woodhull made a fortune on the New York Stock Exchange by advising clients like Vanderbilt. On one occasion he sold some shares short for 150 cents per stock, based on her advice, and earned millions on the deal.

In 1870, Woodhull and Claflin used the money they had made from their brokerage to found a newspaper, the Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly, which at its height had a national circulation of 20,000. Its primary purpose was to support Victoria Claflin Woodhull for President of the United States. It ran for six years, becoming notorious for publishing controversial opinions on sex education, free love, women's suffrage, short skirts, spiritualism, vegetarianism, and licensed prostitution.

In 1872, the Weekly published a story exposing the adultery of Henry Ward Beecher, a renowned preacher of Brooklyn's Plymouth Church. For publishing this scandalous story, Woodhull, Claflin and Col. Blood were arrested and charged with publishing an obscene newspaper and circulating it through the United States Postal Service. It was this arrest and Woodhull's acquittal that propelled Congress to pass the 1873 Comstock Laws, a series of provisions in Federal law that criminalize the involvement of the United States Postal Service, its officers, or a common carrier in conveying obscene matter, crime-inciting matter, or certain abortion-related matter.

Woodhull learned how to infiltrate the all-male domain of national politics and arranged to testify on women's suffrage before the House Judiciary Committee. In December 1870, she submitted a memorial in support of the New Departure to the House Committee. She read the memorial aloud to the Committee, arguing that women already had the right to vote, since the 14th and 15th Amendments guaranteed the protection of that right for all citizens. The logic of her argument impressed some committee members. Suffrage leaders postponed the opening of the 1871 National Woman Suffrage Association's third annual convention in Washington in order to attend the committee hearing. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Isabella Beecher Hooker, saw Woodhull as the newest champion of their cause.

In 1871, Woodhull announced her intention to run for president. She also spoke against the government being all male and proposed the development of a new constitution and the creation of a new government.

Woodhull was nominated for president of the United States by the newly formed Equal Rights Party on May 10, 1872, at Apollo Hall, New York City. Her nomination was ratified at the convention on June 6, 1872, making her the first woman candidate.

Woodhull's campaign was also notable because Frederick Douglass was nominated as its vice-presidential candidate, even though he did not take part in the convention, acknowledge his nomination and did not play any active role in the campaign.

The Equal Rights Party hoped to use the nominations to reunite suffragists with African-American civil rights activists, because the exclusion of female suffrage from the Fifteenth Amendment two years earlier had caused a substantial rift between the groups.

Woodhull received no electoral votes in the election of 1872, and a negligible, but unknown, percentage of the popular vote.

Woodhull again tried to gain nominations for the presidency in 1884 and 1892.

She moved to Great Britain in 1877 where she lectured, published a magazine, and became a champion for education reform in English village schools.

She was active in the pioneering days of female motorists, and was said to have been the first woman to drive a car in Hyde Park, London and in the English country roads.

Seraph Young Ford (1846–1938)

Helen Hamilton Gardener (1853-1925)

Seraph Young Ford (1846–1938)

On February 14, 1870, Seraph Young became, according to many accounts, the first woman in the United States to vote under a women’s equal suffrage law. Two days earlier, Utah (then a U.S. territory) had passed legislation granting women the right to vote. Young, a schoolteacher and the grand-niece of Brigham Young, president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) and Utah’s first governor, became the first woman to cast a ballot when she exercised her newly-granted franchise in a Salt Lake City local election. A few months later in August 1870 during Utah’s general election, approximately 2,000 women voted.

In 1872, two years after she voted for the first time, Seraph Young married Seth L. Ford, who had fought for the U.S. Army during the Civil War. He is buried alongside his wife (Section 13, Grave 89-A) in Arlington National Cemetery.

Helen Hamilton Gardener (1853-1925)

Helen Hamilton Gardener (1853-1925)

Helen Hamilton Gardener (1853-1925)

Helen Hamilton Gardener, a prominent suffragist, was once the highest-ranking woman in the U.S. government. In April 1920, President Woodrow Wilson appointed her as one of three U.S. Civil Service Commissioners, responsible for overseeing nearly 700,000 federal employees. Still, it would be four more months before women gained the right to vote, when Congress certified the 19th Amendment on August 26, 1920.

Gardener had previously served as a vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and she was said to have persuaded President Wilson to support women’s voting rights. She also wrote several books and lectured widely on gender equality and other social issues. Gardener, a well-connected resident of Washington, D.C., played a key role in preserving documents and artifacts from the suffrage movement. These items remain in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 3, Grave 4072.

Ida Wells (1862-1931)

Rosalie Barrow Edge (1877-1962)

Helen Hamilton Gardener (1853-1925)

Pioneering journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) battled sexism, racism, and violence, shedding light on the conditions of African Americans and crusading against lynching.

At 22, Ida bought a first-class ticket on a train from Memphis to Holly Springs and took a seat in the ladies’ car. When the conductor told her to move. Ida resisted, and when he tried to drag her from her seat, she bit his hand.

She sued the railroad for damages and won, but the railroad won on appeal.

In 1886, when she was 24, Ida lost her teaching job after criticizing conditions in the Memphis schools. She decided to become a full-time journalist. Three years later, she became a shareholder in the newspaper Memphis Free Speech and Headlight and its editor. She was the first female co-owner and editor of a Black newspaper in the US.

After she wrote a series of anti-lynching editorials, including one suggesting that white women could find black men appealing, threats were made against her and her family and her newspaper offices were burned.

She relocated to the North and documented 728 lynching cases that occurred between 1884 and 1892, using research by the Chicago Tribune.

She also supported women's right to vote and co-founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago in 1913, the largest Black women’s suffrage organization in Illinois.

She famously spoke before British temperance advocates on May 9, 1894, taking on Frances E. Willard, a leader in the women's suffragette movement who made racist statements in a previous interview. Despite backlash, she persisted and helped Londoners establish the London Anti-Lynching Committee.

Ida marched in the 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, DC, refusing to be segregated in the parade. She was also one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Rosalie Barrow Edge (1877-1962)

Rosalie Barrow Edge (1877-1962)

Rosalie Barrow Edge (1877-1962)

Rosalie Barrow Edge (November 3, 1877 – November 30, 1962) was an American environmentalist.

In 1915 Edge began birdwatching as a way to bond with her husband and her son. After reading of the slaughter of 70,000 bald eagles in the Alaska Territory, she felt it her duty to act.

In 1929, Edge founded the Emergency Conservation Committee (ECC), running it until she died. The ECC emphasized the need to protect all species of birds and animals.

That same year, Edge learned that in order to preserve songbirds, Audubon sanctuaries were killing birds of prey, trapping small mammals and selling their pelts and furs. Edge successfully filed a suit in 1931 against the NAAS to obtain its membership mailing list in order to inform them about the society’s actions.

Edge learned about a ridge on Hawk Mountain in the Appalachian Mountains that hosted an annual shoot targeting hawks and eagles. Edge signed a contract to lease about 1,340 acres of the land in June 1934. That year, Edge and her family traveled to the area on weekends and hired caretakers and an armed former police officer to protect the land, which became Hawk Mountain Sanctuary. Edge eventually purchased it with her own money and funds raised by the ECC, later transferring ownership to the Hawk Mountain Sanctuary Association.

Edge also led grassroots campaigns to create Olympic National Park (1938) and Kings Canyon National Park (1940). She influenced founders of The Wilderness Society, The Nature Conservancy, and Environmental Defense Fund, along with other major wildlife protection and environmental organizations.

Helen Hulick (1908-1989)

Helen Louise Hulick Beebe (December 27, 1908 – March 18, 1989) was an American educator and pioneer of auditory-verbal therapy. In 1938, she made headlines when a judge jailed her for wearing trousers while appearing as a witness in court.

Helen Hulick received her PhD in 1930 from the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton, Massachusetts.

She taught in deaf schools in Oregon and California before returning to the East Coast in 1942.

In 1938, while living in California, she was called as a witness in the trial of two men accused of burgling her home. She chose to wear slacks. The judge disapproved, and told her to come back the following court day wearing a dress.

As she told reporters at the time, “Listen, I’ve worn slacks since I was 15. I don’t own a dress except a formal. If he wants me to appear in a formal gown that’s okay with me. I’ll come back in slacks and if he puts me in jail I hope it will help to free women forever of anti-slackism.”

When she returned still wearing pants, the judge said, “You were requested to return in garb acceptable to courtroom procedure. Today you come back dressed in pants and openly defying the court and its duties to conduct judicial proceedings in an orderly manner. It’s time a decision was reached on this matter and on the power the court has to maintain what it considers orderly conduct.

The court hereby orders and directs you to return tomorrow in accepted dress. If you insist on wearing slacks again you will be prevented from testifying because that would hinder the administration of justice. But be prepared to be punished according to law for contempt of court.”

She returned in her slacks again. The judge ordered her to be jailed for five days for contempt of court.

Newspapers ran her story and her picture, standing proud, smiling, wearing the pants.

Though the judge mandated five days, Helen would spend only a few hours in jail after his decision was overturned. When she returned to court, she did wear a dress, but she made a point of going extra fancy for the occasion.

In 1942, she moved to New York, where she began a twenty-year collaboration with the Viennese speech therapist and psychologist Emil Fröschels. Following his death in 1972, she continued to develop his technique, now known as the auditory-verbal approach. Auditory-verbal therapy is a method for teaching deaf children to listen and speak using hearing technology (hearing aids, auditory implants, and assistive listening devices).

In 1950, she presented her philosophy at the congress of the International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics (IALP) in Amsterdam.

In 1972, the Larry Jarret Memorial Foundation was established to promote Beebe's method of unisensory training and make it available to all hearing-impaired children. Beebe donated her private practice to the foundation in 1978. It later became the Helen Beebe Speech and Hearing Center, a not-for-profit organization. In the early 1980s, the practice taught parents how to use the method at home. Many families came from Europe and South America for a week of intensive training.

Beebe was co-founder and first president of Auditory-Verbal International (AVI) (since 2005, the AG Bell Academy for Listening and Spoken Language), which promoted the auditory-verbal approach, and which trains teachers worldwide. She was a director of the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and the Foundation for Children's Hearing, Education and Research.

She died of heart failure on March 18, 1989, at Easton Hospital in Pennsylvania.

Eunice Shriver (1921–2009)

Eunice Mary Kennedy Shriver (July 10, 1921 – August 11, 2009) was an American social worker, philanthropist, and founder of the Special Olympics. She was the sister of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, U.S. Senators Robert F. Kennedy and Edward Kennedy, and U.S. Ambassador to Ireland Jean Kennedy Smith.

She graduated from Stanford University in 1943 with a Bachelor of Science degree in sociology. After her graduation, she worked with the U.S. Justice Department as executive secretary for a project dealing with juvenile delinquency. Kennedy then served as a social worker at the Federal Industrial Institution for Women for one year before moving to Chicago in 1951 to work with the House of the Good Shepherd women's shelter and Chicago Juvenile Court.

Shriver became executive vice president of the Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Foundation in 1957 and shifted the organization's focus to research on the causes and treatments of intellectual disabilities.

Shriver championed the creation of the President's Panel on Mental Retardation in 1961, which was significant in the movement from institutionalization to community integration in the U.S. and throughout the world. Shriver was a key founder of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), a part of the National Institutes of Health in 1962.

In 1962, Shriver founded Camp Shriver, a summer day camp which allowed children and adults with intellectual disabilities to participate in a variety of sports and physical activities. From that camp came the concept of Special Olympics. In 1968 the First International Special Olympics Summer Games was held in Chicago's Soldier Field where 1,000 athletes from 26 states and Canada competed. In her speech at the opening ceremony, Shriver said, "The Chicago Special Olympics prove a very fundamental fact, the fact that exceptional children — mentally disabled children — can be exceptional athletes, the fact that through sports they can realize their potential for growth." Since that time, nearly three million athletes have participated.

Shriver was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1984 by President Ronald Reagan for her work on behalf of persons with disabilities.

For her work in nationalizing the Special Olympics, Shriver received the Civitan International World Citizenship Award. She is the only woman to appear on a U.S. coin while still living. Her portrait is on the 1995 commemorative silver dollar honoring the Special Olympics.

In 1998, Shriver was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

Although Shriver was a Democrat, she was a vocal supporter of the anti-abortion movement, supporting several anti-abortion organizations, Feminists for Life of America, the Susan B. Anthony List, and Democrats for Life of America.

Johnnie Lacy (1937-2010)

Johnnie Lacy (1937–2010) was a Black activist for the independent living movement.

Lacy contacted polio and was paralyzed at 19 while attending nursing school. She applied to San Francisco State University to study speech-language pathology, but was blocked from the program due to her disability.

She was eventually admitted after advocating for her rights, but was not allowed to participate in the graduation ceremony or officially be part of the school.

In 1981, Lacy helped found the Center for Independent Living in Berkeley, California — one of the first organizations in the country to empower people with disabilities to lead independent lives. She later served as director of the Community Resources for Independent Living (CRIL), which connects individuals with disabilities to resources like transportation, housing assistance, and advocacy services.

Lacy’s efforts helped pave the way for the Americans with Disabilities Act,which affirms and protects the rights of individuals with disabilities.

Marsha P. Johnson (1945-1992)

Judith Ellen "Judy" Heumann (1947-2023)

Marsha P. Johnson (August 24, 1945 – July 6, 1992) was an American gay liberation activist and drag queen. She was one of the prominent figures in the Stonewall uprising of 1969.

Johnson was a member of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and co-founded the activist group Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). Johnson was known as the "mayor of Christopher Street" for being a welcoming presence in Greenwich Village. Beginning in 1987, she was an AIDS activist with ACT UP.

Johnson's body was found in the Hudson River in 1992. While initially ruled a suicide by the New York City Police Department (NYPD), controversy and protest followed the case, resulting in it eventually being re-opened as a possible homicide.

Judith Ellen "Judy" Heumann (1947-2023)

Judith Ellen "Judy" Heumann (1947-2023)

Judith Ellen "Judy" Heumann (1947-2023)

Judith Ellen "Judy" Heumann (December 18, 1947 – March 4, 2023) was an American disability rights activist activist, known as the "Mother of the Disability Rights Movement". Heumann was a lifelong civil rights advocate for people with disabilities.

Heumann and several friends founded Disabled in Action (DIA), an organization focused on securing the protection of people with disabilities under civil rights laws through political protest.

Heumann helped develop legislation that became the Individual with Disabilities Education Act while she was serving as a legislative assistant to the chairperson of the U.S Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare.

In 1977, U.S. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Joseph Califano refused to sign meaningful regulations for Section504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the first U.S. federal civil rights protection for people with disabilities.

Demonstrations took place in ten U.S. cities on April 5, 1977, including a sit-in at the San Francisco office of the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. This sit-in, which was led by Heumann and organized by Kitty Cone, lasted 28 days, with about 125 to 150 people refusing to leave.

Califano signed both the Education of All Handicapped Children regulations and the Section 504 regulations on April 28, 1977.

Heumann served as Assistant Secretary of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services at the United States Department of Education from 1993 to 2001.

From 2002 to 2006, Heumann served as the World Bank Group's first Advisor on Disability and Development .

In 2010, Heumann became the Special Advisor on International Disability Rights for the U.S. State Department. She was the first person to hold this role, and served from 2010 to 2017.

From September 2017 to April 2019, Heumann was a Senior Fellow at the Ford Foundation.

Jazzie Collins (1958-2013)

Judith Ellen "Judy" Heumann (1947-2023)

Judith Ellen "Judy" Heumann (1947-2023)

Jazzie Collins (September 24, 1958 – July 11, 2013) was a Black trans woman activist who fought for transgender rights, disability rights and economic equality in San Francisco.

Collins transitioned in her late 40s.

In 2002, Collins became a vocal advocate for minorities including seniors, people with disabilities, and members of the LGBTQ+ community.

Collins served on the Lesbian Gay Transgender Senior Disabled Housing Task Force. She was also an organizer for Senior and Disability Action, an organization that helps seniors and people with disabilities to fight for affordable housing, health care, and transit.

Collins worked to help raise the minimum wage in San Francisco to $8.50 in 2003 — the highest minimum wage in the country at the time.

The first homeless shelter in the United States built specifically for the adult LGBT community was opened in 2015 in San Francisco and named Jazzie's Place in honor of Collins.

Women in The Military and government

Anna Maria Lane (1755–1810)

Albert Cashier/Born Jenni Irene Hodgers (1843-1915)

Anna Etheridge Hooks, U.S. Army (1839–1913)

Anna Maria Lane (1755–1810) dressed as a man to fight with the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War alongside her husband. She was later awarded a pension for her courage in the Battle of Germantown.

Lane and her husband John joined the Continental Army in 1776, fighting in campaigns in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Georgia. On October 3, 1777, they both served under George Washington in the Battle of Germantown, where Anna Maria was severely wounded, leaving her lame for life.

Anna Maria continued fighting alongside her husband in the Virginia Light Dragoons and was with him when he was wounded in the Siege of Savannah in 1779. They both served until 1781.

In 1808, Governor William H. Cabell asked the General Assembly to give pensions to disabled male soldiers, as well as a few women. Cabell specifically mentioned Anna Maria Lane, writing that she was "very infirm, having been disabled by a severe wound which she received while fighting as a common soldier, in one of our Revolutionary battles, from which she never has recovered, and perhaps never will recover." Anna Maria Lane was given a pension of $100 a year for life in recognition of the fact that she, "in the Revolutionary War, performed extraordinary military services at the Battle of Germantown, in the garb, and with the courage of a soldier."

Anna Etheridge Hooks, U.S. Army (1839–1913)

Albert Cashier/Born Jenni Irene Hodgers (1843-1915)

Anna Etheridge Hooks, U.S. Army (1839–1913)

For her service as a U.S. Army nurse in the Civil War, Anna Etheridge was one of only two women to earn the Kearny Cross, awarded to Union soldiers who had displayed meritorious, heroic or distinguished acts while in the face of an enemy force.

She participated in 32 battles, including First and Second Bull Run, Williamsburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. She was noted for removing wounded men from combat.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 15, Grave 710.

Albert Cashier/Born Jenni Irene Hodgers (1843-1915)

Albert Cashier/Born Jenni Irene Hodgers (1843-1915)

Albert Cashier/Born Jenni Irene Hodgers (1843-1915)

Albert D. J. Cashier (December 25, 1843 – October 10, 1915), born Jennie Irene Hodgers, was an Irish-born American soldier who served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Cashier adopted the identity of a man before enlisting, and maintained it until death. Cashier was one of at least 250 soldiers who were assigned female at birth and enlisted as men to fight in the Civil War.

According to later investigation by the administrator of Cashier's estate, Albert Cashier was born Jennie Hodgers in County Louth, Ireland, on December 25, 1843. Even before the advent of the war, Hodgers adopted the identity of Albert Cashier in order to live independently. Sallie Hodgers, Cashier's mother, was known to have died prior to 1862, by which time Albert had traveled as a stowaway to Belvidere, Illinois, and was working as a farmhand to a man named Avery.

On August 6, 1862, the eighteen-year-old enlisted in the 95th Illinois Infantry for a three-year term using the name "Albert D.J. Cashier" and was assigned to Company G. Cashier easily passed the medical examination because it consisted of showing one's hands and feet. Cashier's fellow soldiers recalled that Cashier was reserved and preferred not to share a tent.

After being shipped out to Confederate strongholds in Columbus, Kentucky and Jackson, Tennessee, the 95th was ordered to Grand Junction where the regiment became part of the Army of the Tennessee under General Ulysses S. Grant.

The regiment fought in approximately forty battles, including the Siege of Vicksburg. During this campaign, Cashier was captured while performing reconnaissance, but managed to escape and return to the regiment.

Cashier fought with the regiment until honorably discharged on August 17, 1865, when all the soldiers were mustered out.

After the war, Cashier continued to live and work as a man.

For over forty years, Cashier lived in Saunemin, IL and was a church janitor, cemetery worker, and street lamplighter. Living as a man allowed Cashier to vote in elections and claim a veteran's pension under the same name. Pension payments started in 1907.

In later years, Cashier was friends with the Lannon family. The Lannons discovered their friend's sex when Cashier fell ill, but did not to make their discovery public.

In 1911, Cashier, who was working for State Senator Ira Lish at the time, was hit by the senator's car, resulting in a broken leg. A physician found out Cashier's secret in the hospital, but said nothing. No longer able to work, Cashier was moved to the Soldiers and Sailors home in Quincy, Illinois, where many friends and fellow soldiers from the Ninety-fifth Regiment visited. Cashier lived there until their mind began to deteriorate, and was moved to the Watertown State Hospital for the Insane in East Moline, Illinois, in 1914. Attendants at the Watertown State Hospital discovered Cashier's sex, at which point Cashier was made to wear women's clothes again. In 1914, Cashier was investigated for fraud by the veterans' pension board; the board decided that payments should continue for life former after comrades confirmed that Cashier was the person who had fought in the Civil War.

Albert Cashier died on October 10, 1915, and was buried in uniform with an official Grand Army of the Republic funerary service, with full military honors, under a small tombstone inscribed with ”Albert D. J. Cashier, Co. G, 95 Ill. Inf.”. In 1977 local residents erected a larger second headstone, inscribed with both names, on the same plot.

Namahoyke "Namah" Curtis, U.S. Army (1861–1935)

Namahoyke "Namah" Curtis, U.S. Army (1861–1935)

Albert Cashier/Born Jenni Irene Hodgers (1843-1915)

Namahyoke Curtis, known as Namah, was a prominent African American nurse in late-19th-century Washington, D.C.

During the Spanish-American War (1898), the Surgeon General assigned her to recruit other Black women to serve as U.S. Army contract nurses. She recruited as many as 32 Black nurses for the war effort. Curtis was of African American, European and American Indian descent, and she married Dr. Austin Curtis, a leading Black physician and the superintendent of Freedmen’s Hospital in D.C.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 21, Grave 15999-A-1. She is buried in the “Nurses' Section,” which contains the gravesites of many military nurses and the Spanish-American War Nurses Memorial.

Jane Delano, U.S. Army (1862–1919)

Namahoyke "Namah" Curtis, U.S. Army (1861–1935)

Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee, U.S. Army (1864–1940)

A distant relative of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jane Delano served as superintendent of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps from 1909 to 1912, and in 1909 founded the American Red Cross Nursing Service.

By the outbreak of World War I, the American Red Cross Nursing Service had more than 8,000 registered and trained nurses ready for emergency response. Delano was on a Red Cross mission in France when she died in 1919; her last words reportedly were, "I must get back to my work." She was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and reinterred a year later in the "Nurses' Section" of Arlington National Cemetery.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 21, Grave 6.

Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee, U.S. Army (1864–1940)

Namahoyke "Namah" Curtis, U.S. Army (1861–1935)

Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee, U.S. Army (1864–1940)

Dr. Anita McGee received her medical degree from Columbian College (now George Washington University) in 1892.

Her organizing ability led to her appointment, during the Spanish-American War of 1898, as the only woman acting assistant surgeon in the Army, placed in charge of the Army's nurses. She strongly advocated a permanent nursing corps, and in 1901 Congress authorized the creation of the Army Nurse Corps.

Dr. McGee also led efforts to erect the Spanish-American War Nurses Monument at Arlington National Cemetery, dedicated in 1905.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 1, Grave 526B.

Dr. Ollie Josephine Prescott Baird Bennett, U.S. Army (1874–1957)

Dr. Ollie Josephine Prescott Baird Bennett, U.S. Army (1874–1957)

Dr. Ollie Josephine Prescott Baird Bennett, U.S. Army (1874–1957)

After earning an M.D. from Boston University Medical School, Ollie Josephine Prescott Baird (later Baird Bennett, following her 1934 marriage) signed a contract with the Army Medical Corps in 1918.

At the time, women physicians could serve with the Medical Corps only as contract surgeons—civilians who worked for the Army but were not in the Army, received lower salaries, no military benefits, and no formal rank or commission. Like many other women contract physicians during the World War I era, Baird served as an anesthetist. She supervised two operating rooms at Fort McClellan (Alabama) and trained women in the Army Nurse Corps, as well as Army enlisted men. She was also appointed to the War Industries Board as supervisor of health for more than 1,000 female employees. During the interwar years, Baird Bennett opened a private medical practice in Washington, D.C. In March 1943, she testified before Congress to support commissioning female physicians in the Army and Navy. The efforts of Baird Bennett and other advocates proved effective.

On April 16, 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Sparkman-Johnson Bill, which formally allowed women to earn commissions in the Army and Navy Medical Corps.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 10, Grave 10938-LH.

Elizebeth Smith Friedman (1892–1980)

Dr. Ollie Josephine Prescott Baird Bennett, U.S. Army (1874–1957)

Dr. Ollie Josephine Prescott Baird Bennett, U.S. Army (1874–1957)

Elizebeth Smith Friedman was one of the leading cryptologists of the 20th century — and one of the first women employed as a U.S. government codebreaker.

After graduating from Hillsdale College with a degree in English literature, she was working at the Newberry Research Library in Chicago when she was recruited to work at Riverbank, a private think tank that served as the U.S. government's unofficial cryptologic laboratory during World War I. At Riverbank, she met her husband, William F. Friedman, also known for his work in cryptology.

During the 1920s through 1940s, she worked for numerous U.S. government agencies, including the Treasury Department, where she cracked the codes of international alcohol and drug smugglers' messages during Prohibition. In the 1950s, she applied her cryptanalytic skills to the work of William Shakespeare, authoring the award-winning book "The Shakespeare Ciphers Examined." Elizebeth and William Friedman are buried together; their epitaph states, "Knowledge is power."

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 8, Grave 6379-A.

Joy Bright Hancock, U.S. Navy (1898–1986)

Dr. Ollie Josephine Prescott Baird Bennett, U.S. Army (1874–1957)

Beatrice V. Ball, U.S. Coast Guard (1902–1963)

Captain Joy Bright Hancock’s service was instrumental to expanding women’s opportunities in the military.

During World War I, Hancock enlisted in the Navy as a yeoman (F) first class; she served as a courier at the U.S. Naval Air Station in Cape May, New Jersey. She left the military when the war ended, but worked as a civilian for the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics. During World War II, after President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized creation of the Navy Women’s Reserve, or WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), in 1942, Hancock was commissioned as a lieutenant and served as a liaison between the Bureau of Aeronautics and the WAVES. She became director of the WAVES in 1946.

Hancock also played an important role in getting Congress to pass the Women Armed Services Integration Act of 1948, which secured women a permanent place in the military during peacetime. That year, she became one of the first six women sworn into the regular Navy.

In 1972, Captain Hancock published her autobiography, “Lady in the Navy,” recounting her own experiences as well as the history of women in the Navy. She is buried with her husband, U.S. Navy Vice Admiral Ralph A. Ofstie.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 30, Grave 2138-RH.

Beatrice V. Ball, U.S. Coast Guard (1902–1963)

Beatrice V. Ball, U.S. Coast Guard (1902–1963)

Beatrice V. Ball, U.S. Coast Guard (1902–1963)

Cmdr. Beatrice Ball served as a senior officer in SPAR, the U.S. Coast Guard women's reserve, created in November 1942 to help alleviate manpower shortages during World War II. She was the first SPAR member assigned to intelligence work. The name of the unit is a contraction of the Coast Guard motto, "Semper Paratus — Always Ready."

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 8, Grave 115-RH.

Rear Admiral Grace Hopper (1906-1992)

Beatrice V. Ball, U.S. Coast Guard (1902–1963)

Rear Admiral Grace Hopper (1906-1992)

Rear Admiral Grace Hopper (December 9, 1906 – January 1, 1992) was an American computer scientist, mathematician, and United States Navy rear admiral. She was the first to devise the theory of machine-independent programming languages, and used this theory to develop the FLOW-MATIC programming language and COBOL, an early high-level programming language still in use today.

In 1943, during World War II, she joined the United States Naval Reserves. She was assigned to the Bureau of Ordinance Computation Project. There she became the third programmer of the world’s first large-scale computer called the Mark I. She mastered the Mark I, Mark II, and Mark III. During her career she mastered the UNIVAC I, the first large-scale electronic computer, and created a program that translated symbolic math codes into machine language. This breakthrough allowed programmers to store codes on magnetic tape and re-call them when they were needed — essentially the first compiler.

In 1966, Hopper retired from the Naval Reserves as a Commander, but was called back to active duty one year later at the Navy’s request, to help standardize its computer programs and their languages. She was promoted to Captain in 1973 by Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, Jr., Chief of Naval Operations. And in 1977, she was appointed special advisor to Commander, Naval Data Automation Command (NAVDAC), where she stayed until she retired. At the age of 76, she was promoted to Commodore by special Presidential appointment. Her rank was elevated to rear admiral in November 1985, making her one of few women admirals in the history of the United States Navy.

By the time of her death in 1992, Hopper was renowned as a mentor and a giant in her field, with honoree doctorates from over 30 universities. She was laid to rest with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

Juanita Hipps, U.S. Army (1912–1979)

Beatrice V. Ball, U.S. Coast Guard (1902–1963)

Rear Admiral Grace Hopper (1906-1992)

During World War II, Lt. Col. Juanita Hipps served as a U.S. Army nurse in the Philippines and chronicled her experiences in a bestselling book, "I Served on Bataan" (1943). Reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel, Hipps also helped to establish the Army Air Corps flight nurse program.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 21, Grave 769-1.

Catherine Murray, U.S. Marine Corps (1917–2017)

Betty Jane "BJ" Williams, U.S. Air Force (1919–2008)

Betty Jane "BJ" Williams, U.S. Air Force (1919–2008)

On December 7, 1941, Catherine Murray decided to enlist in the military after hearing President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s radio announcement of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

She served with a motor transport unit in the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve. After World War II, Murray was one of 50 women who continued to actively serve in the Marines. For the next two decades, she served at 15 duty stations and assumed a wide range of responsibilities. While stationed at Quantico, she wrote the manuals used to train future female Marines. In 1962, Murray became the first enlisted female Marine to retire from active duty, at the rank of master sergeant. She died in 2017 at the age of 100.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 60, Grave 1170.

Betty Jane "BJ" Williams, U.S. Air Force (1919–2008)

Betty Jane "BJ" Williams, U.S. Air Force (1919–2008)

Betty Jane "BJ" Williams, U.S. Air Force (1919–2008)

Betty Jane “BJ” Williams was a pioneering pilot, educator and promoter of aviation. She earned her private pilot’s license in 1941, and during World War II, she served in the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) as an engineering test pilot.

After the WASP was disbanded in December 1944, Williams continued her aviation career as a commercial pilot, flight instructor and aerospace engineering technical writer.

Commissioned as an Air Force officer during the Korean War, she produced training and motivational programs as part of the Air Force’s first video production squadron. She then served in the Air Force Reserves as a public affairs officer, retiring in 1979 with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 54, Grave 2972.

Ruth Lucas, U.S. Air Force (1920–2013)

Betty Jane "BJ" Williams, U.S. Air Force (1919–2008)

Jeanne M. Holm, U.S. Air Force (1921–2010)

During World War II, Ruth Lucas enlisted in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) and became one of the few Black women to attend what is now the Joint Forces Staff College in Norfolk, Virginia. She transferred from the Army to the Air Force in 1947, where she stayed for the remainder of her military career.

While stationed in Tokyo, Japan as chief of the Air Force Awards Division (1951-1954), she spent much of her free time teaching English to Japanese students. Upon returning to the United States, she earned a graduate degree in educational psychology from Columbia University. She was then transferred to Washington, D.C. to develop educational programs for service members. In 1968, she became the first Black woman promoted to colonel in the Air Force. She also received the Defense Meritorious Service Medal, awarded for outstanding non-combat service.

She is interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 64, Grave 6031.

Jeanne M. Holm, U.S. Air Force (1921–2010)

Mary Crawford Ragland, U.S. Army (1922–2010)

Jeanne M. Holm, U.S. Air Force (1921–2010)